Meeting Ringo Starr: On Not Living Up to the Moment

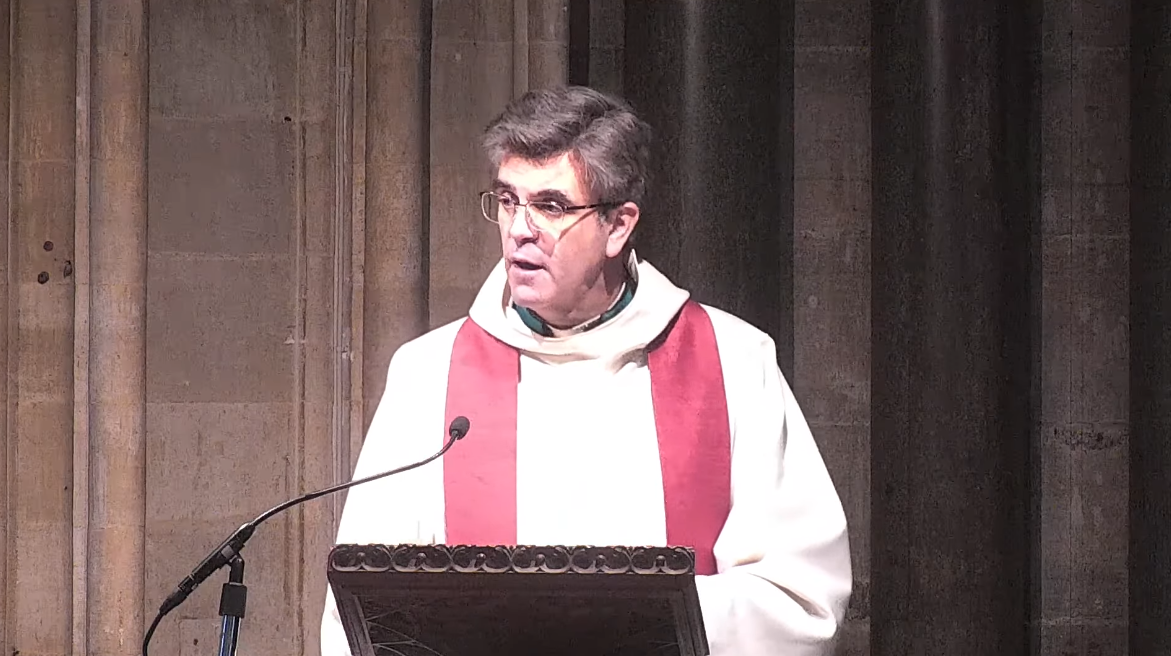

Sunday 15 February 2026, The Sunday next before Lent , 10.30am Eucharist

The Very Reverend Nicholas Papadopulos, Dean of Salisbury

2 Peter 1: 16–end

Matthew 17: 1–9

“Lord, it is good for us to be here; if you wish, I will make three dwellings here, one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah”

Some of you know of my lifelong affection for – indeed, obsession with – The Beatles and their music. So you will appreciate that the day I met Ringo Starr was one of the greatest days of my life. It was utterly unexpected, of course. I stepped out of the side door of the parish church in Westminster where I was the Vicar, and there he was, walking through our car park. I had less than a split second. What should I say? ‘I think you’re the most consequential drummer in history…your music has been the soundtrack of my life…I have all your records’? But, dumbstruck, I settled for proffering my hand. With the ease that kept the band together for so long, Ringo crooked his arm and proffered it. ‘Give me an elbow, man’ he said. ‘I don’t want to catch the flu’. I bumped elbows with a Beatle, and he was gone.

It was one of the greatest days of my life. But it should have been greater. I did not rise to the occasion; I did not live up to the moment. I had the chance to tell Ringo Starr that I loved him – and I didn’t.

In his series of sermons on the Transfiguration John Hacket, seventeenth century Bishop of Lichfield, argued that offering to build dwellings for Jesus, Moses, and Elijah was “…the greatest error that St Peter committed”. Hacket’s verdict has always struck me as somewhat harsh.

It is true that, according to St Luke, the Blessed Virgin Mary responds to the message of the Archangel that she is going to bear a son with a triumphant hymn of praise. We still sing the Magnificat every evening. It is true that, according to St Luke, the elderly priest Zechariah responds to the birth of his own son with another triumphant hymn of praise. We still say the Benedictus every morning.

And it is also true that, judged by these exacting poetic standards, Peter’s response is sub-optimal, even in St Luke’s telling of it. Peter does not respond to the mountain-top scene of unearthly glory with a paean of awestruck wonder. No Song of Saint Peter has been borne heavenwards on the lips of Christians for two millennia. There is the second letter that bears Peter’s name, and perhaps it makes up for some of his want of immediate appropriate lyrical wordsmithery: ‘We ourselves heard this voice come from heaven, while we were with him on the holy mountain’. But the scholarly estimate is that the letter was written at least fifty years after the event it describes. So at best Peter had what can only be described as an abnormally delayed reaction to beholding his transfigured Lord. And, in fact, the scholarly consensus is that Peter was probably not the letter’s author.

Which leaves us with: “Lord, it is good for us to be here; if you wish, I will make three dwellings here, one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah”.

His greatest error? Peter was a Galilean fisherman. He was good with his hands. He was used to mending boats, gutting fish, and patching up nets. Brought face to face with the light of Heaven he reverts to type. In the face of the inexplicable and overwhelming what can he do? Make some ‘dwellings’ – obviously!

Every year, without fail, it’s a massive relief to me that we read a Gospel account of the Transfiguration on the Sunday next before Lent. It’s a massive relief because the next time we encounter Jesus on a hilltop between two others the scene will be very different: today we are permitted to catch a glimpse of the divine before we descend to the wilderness and begin the weeks of penitence and fasting that stretch rather bleakly before us. And it’s also a massive relief because of St Peter’s sub-optimal response.

On the mountain-top Heaven has been laid bare. The created order is suffused with uncreated light. Giants of Israel’s history walk the Earth once again. And Peter manifestly fails to rise to the occasion. He does not do what the sublime surroundings seem to demand. He fails to utter resonant words that will be set to music by everyone from Tallis to Halls. He doesn’t even leave the mountain-top with a serene countenance and a steadfast heart, forever a changed man. No. He reverts to type. In the face of the inexplicable and overwhelming he offers to get out his chisel, his mallet and his plane, and he offers to knock something together. And then he descends to the plain and proceeds to deny having ever known the one whose glorious identity has been revealed to him on the mountain top.

And this is a massive relief because it reminds me that I have at least one thing in common with St Peter. And it’s not my DIY skills, which are non-existent. If I fail to rise to the occasion when confronted with one of only two living Beatles, how much more spectacularly do I fail to rise to God’s occasion – to the minute-by-minute grace of the God who loved the world so much that he gave his only Son that the world might believe through him?

Lent brings this reality into focus. I receive ash on my forehead and daub it on the foreheads of others and wonder what’s for dinner as I do so. I hear the gorgeous music of our choir (from Tallis to Halls) and I walk in solemn procession behind them, only to obsess internally about impossible neighbours, difficult meetings, and unanswered emails. I order books and I make vows about abstinence and study, only to break them. In short, I revert to type, just as St Peter did. Only, my type is an unflattering and obnoxious type, distracted, hungry – and hangry.

But…but…whoever said that I was expected to rise to God’s occasion or live up to God’s moment? I did. Perhaps the expectation that I have of myself is just one more example of human vanity, one more instance in which I’m convinced that it’s all about me, about how well I do, about how exactly I measure up.

Thank God, it’s not. Lent, however imperfectly observed, leads us to Passiontide, and at Passiontide God in Jesus does not rise to the occasion. He descends to it. He descends to the scourge, to the nails, to the crown of thorns. He comes down the mountain and joins us in the darkness of the plain. And that, my dear sisters and brothers, is why there is hope. Lent is coming. Alleluia, alleluia, alleluia!